International Veterinary Outreach

Tuesday, February 25, 2014 at 12:01PM

Tuesday, February 25, 2014 at 12:01PM Winner, Experiences

Tracy Huang, UC Davis

A pause, as I turn to take it all in – the hustle and bustle of my colleagues getting more fluids, drawing up vaccines, adjusting the headlamp for intubation, and watching the autoclave on the stovetop. This is Cosiguina, a rural community in northwestern Nicaragua, and day 3 of the December 2013 clinic trip with International Veterinary Outreach (IVO).

IVO is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization founded and run by veterinary students. In the Fall of 2011, a group of visionary and dedicated veterinary students from UC Davis decided to found an organization to serve animals in rural communities that otherwise would not receive veterinary care. With the help and guidance of Dr. Eric Davis, founder of HSVMA-RAVS and RVETS, IVO became a source of veterinary care for rural communities in northwestern Nicaragua. Twice a year, a group of veterinary students, technicians, and veterinarians make the trek out to these communities to provide wellness exams, preventative care, treatments, and spay/neuter surgeries for both the large and small animal populations. Over the course of two years, IVO has been to Nicaragua five times, and the change and impact is apparent.

My first trip to Nicaragua with IVO was back in the summer of 2012 as a student volunteer. It was an experience that left me dazed and confused. I was supposed to feel good about giving back to the communities. Instead, I ended the trip skeptical about the effects of our work, saddened by the conditions of the animals, and deeply struck by the poverty of the communities. Working in a culture with different priorities, a different mentality, and different resources presented so many challenges. Yet, I was stimulated. So, I took on the role of co-president and purchased my second, third, and fourth plane ticket back to Nicaragua.

During our clinic trips, we set up field clinics in a different community every day. As we continue to return to Nicaragua, there are communities that we regularly return to every six months and communities that we have only begun to work in. Cosiguina is one such community, located close to the border of Honduras. The lack of veterinary services and outreach in Cosiguina is apparent. Dogs that have never before been on leash are understandably much more fearful and difficult to handle, and their poor body conditions are striking. Our surgery board is barely filled with spays and neuters, as there is a lack of understanding about what the surgeries are for and their health and welfare benefits. Cosiguina is what the other communities that we have first worked in started out as – with heavy skepticism from the community about the importance and benefits of sterilization, limited access to veterinary care for their animals, and rampant pet overpopulation.

While there are still these problems in the other communities that we have regularly returned to, we have slowly made progress – progress evident in the growing receptivity of the community to our veterinary recommendations and to pet sterilizations. As we gradually establish relationships with the communities, we see increasing numbers of patients with each trip. In addition, there are notable changes in individual lives, evident in the dogs that return to our clinic for preventative care with the same leashes we provided them in the past, in the owners who bring their dogs back to us every six months for another treatment for their dogs’ transmissible venereal tumor (TVT), and in the woman who walked four kilometers down a hot, dusty road to our next clinic site for her dog’s spay. All this is proof of progress and reason for me to continue to return.

With every trip, we learn more about the needs of the communities that we work in. We implement different educational initiatives to help address these needs, such as basic nutrition, reasons to spay/neuter, and the importance of flea/tick preventatives. In addition, we recruit local veterinary students and veterinarians to promote an exchange of ideas and to better understand the role of veterinary professionals in Nicaragua. It has been through these initiatives that we have been able to and hope to continue to make progress.

Back in Cosiguina, our surgery tables may not be busy, but this is a place we will have to revisit because our work here has only just begun. So, I pick up a chart, grab a leash, and walk out in search of my next patient.

Dr. Eric Etheridge and UC Davis veterinary student, Jamie White, vaccinate a pig in a rural community in northwestern Nicaragua.

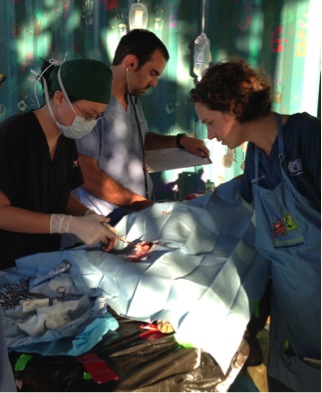

UC Davis veterinary student, Matt LeShaw, gain experience monitoring anesthesia, while Dr. Jean Goh, director of Spay & Neuter Clinic at the San Francisco SPCA, perform a canine spay in the field.